Origins of the Boston Biotech Working Group to Address the Underrepresentation of Women Faculty as Board Members and Founders of Biotech Start-ups

Nancy HopkinsIntroduction

Many MIT faculty, particularly in Science and Engineering, engage in entrepreneurial activities. This includes founding companies and serving on their boards of directors or scientific advisory boards. In some fields these activities are an important part of faculty’s professional life, because they provide exposure and access to cutting-edge technologies and information that benefit both faculty and their trainees.

Many reports have documented that, even today, women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and other fields are often underrepresented in these activities relative to their numbers in the pipeline. Other studies have been conducted to understand why this is the case. While the reasons can be varied and context dependent, common findings point to lack of access to venture capital (VC) funding networks (1). This lack of access, and the consequent lack of participation, can pose at least a two-fold problem: it can deprive women faculty and women trainees of important professional opportunities, and it can prevent them from translating and commercializing their discoveries for public benefit.

In the mid 1990s, I chaired the first Committee on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT, which addressed the marginalization and exclusion of women faculty within the university. In the course of that work, I received a mailing that listed 99 scientists from the Boston area who had been funded to start biotech companies. Remarkably, only one of the 99 people on the list, a professor at Harvard Medical School, was a woman. At the time, it was well beyond the ambit of our committee to address the underrepresentation of women at the interface of academia and industry, but in 1996 we produced an internal Committee Report to the Dean of Science in which we flagged the issue for attention (2).

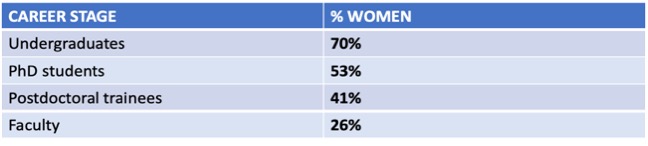

Apparently, little changed over the next 15 years. In 2011, a woman from Harvard Business School reported to me that she had seen a list of 100 scientists in the Boston area funded by venture capital (VC) to start Biotech companies. Only one of 100 was a woman. The woman who reported this to me wanted to know how this was possible, given that by then, 50% of PhDs in Biology had long been awarded to women, and women comprised roughly 25% of university biology faculties (Table 1).

[Data provided by Lydia Snover and Sonia Liou, Institutional Research, MIT]

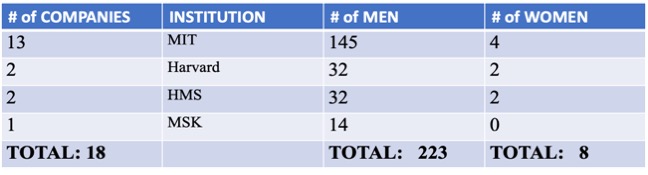

This woman’s query prompted me to wonder how many women and men on the faculties of biology departments at MIT, Harvard, and comparable institutions had been involved with biotech start-ups as founders or board members. Using company data from the internet and discussions with faculty, I conducted a survey and found that it was rare for women faculty in biology not only to found biotech companies, but also to be invited to serve on their boards of directors (BODs) or even the scientific advisory boards (SABs) of companies founded by their male colleagues. This was true even though there were women on these faculties who were equally or more qualified scientifically than the men who had been asked to serve in these roles. My informal results (Table 2) were described in 2013 in a Nature news article titled, “Barred from the boardroom” (3).

(1 company). Data collected in 2013. 84 of the 231 people are full-time faculty. Of 84 full-time faculty, 80 are men, 4 are women = 4.8%.

Preliminary Data Attracts Powerful Allies and Leads to the Boston Biotech Working Group

My informal survey results surprised our colleague Sangeeta Bhatia, a bioengineer and professor in MIT’s School of Engineering (in EECS and IMES). An entrepreneur who has founded companies, and a person committed to supporting the careers of women in STEM, Bhatia promptly conducted her own informal survey of women on MIT’s engineering faculty. She identified a number of them who had founded companies, but these women reported that they were seldom asked to co-found companies with male colleagues, and some perceived that it was more difficult for women to raise comparable start-up funding than for men. Importantly, when Ann Arvin, then the vice provost and dean of research at Stanford, conducted a similar study at Stanford, her findings were strikingly similar to ours (4).((In the past few years, Arvin recently told us, women faculty in biology seem to be participating more actively in commercialization, (pers comm.)))

The data had obviously identified a pattern of professional barriers for MIT women faculty interested in translating their research discoveries and for women trainees, particularly in biological sciences. Some women faculty said they knew so little about commercialization that they were unable to advise graduate students and postdocs who expressed interest in biotech. A woman postdoc reported that the head of her lab gathered the male postdocs in his office at lunchtime for closed-door discussions about companies, while leaving the female postdocs sitting outside. Women faculty who had been interested in founding companies reported being unable to navigate the process on their own, even when it came to patenting their discoveries. A male colleague with experience in founding biotech start-ups pointed out that this inequity means that men on these faculties are earning much more than women. Faculty profits from commercialization are not infrequently in the many millions of dollars, and even serving on boards can double a faculty member’s salary.

In November of 2017 I teamed up with my MIT colleague Harvey Lodish (Biology), who has extensive experience in founding biotech companies, to write an op-ed for the Boston Globe calling attention to this issue (5).

As important as they’ve been for raising awareness and explaining the problem, however, the publications I’ve mentioned above cannot fix the problem. The critical challenge is how to rapidly fix such an entrenched and still largely invisible problem at the interface of the university and private industry.

In September of 2018, I received a Lifetime Achievement award from Xconomy, a news and media company concerned with the biotech and tech industries – something of an irony, given that I had publicly brought the industry to task for the stunning lack of diversity in the leadership and governance of biotech start-up companies. I was introduced by Sangeeta Bhatia.

In my acceptance speech, I talked about my life in science and about the enormous progress I had seen for women faculty in STEM thanks to MIT’s efforts. I contrasted that change with what I perceived to be so little progress in diversifying the leadership in biotech, and I presented some of the data I had collected. Seated in the audience that night, at a table with Bhatia and me, was Susan Hockfield, MIT’s president emerita. Immediately recognizing the implications of the data, Hockfield offered to join with us to devise solutions to achieve two goals: 1) increase the number of women faculty serving on boards of biotech start-ups; and 2) open avenues to commercialization for women faculty interested in founding companies. She made clear that she felt we needed to achieve both goals rapidly.

Boston has a robust VC industry, and MIT has a superb TLO (Technology and Licensing Office). Today, a typical MIT-founded biotech start-up gets its start when a discovery in an MIT lab is patented by the TLO and licensed to the start-up. One or two additional faculty, or a postdoc involved in the discovery, may also be co-founders. The boards of such companies typically include VCs, the faculty founder(s), and prominent scientists chosen by the VCs. SAB members are noted scientists in the field. We learned that when entrepreneurs found a company and create its BOD, they frequently draw on a network of venture capitalists and faculty, many of whom have founded multiple companies individually and together and almost all of whom are men. As the industry has matured, moreover, faculty with experience in biotech have become more likely to be selected for these positions, making it even less likely for women faculty to participate.

Hockfield, Bhatia, and I assembled a list of experts and stakeholders to help us achieve our two goals. It included venture capitalists; faculty who had founded biotech companies; academic and hospital administrators; local and state officials; policymakers committed to fostering the biotech industry in Kendall Square, Boston, and across Massachusetts; members of the media; and the heads of MIT’s TLO and Institutional Research (IR) offices. The leadership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences also made the effort possible, by hosting a series of dinners for the group, which came to be known as the Boston Biotech Working Group (BBWG).

Data Collection, VC Engagement, and a Future Founders Initiative

BBWG dinners, the first held in December of 2018, were inspiring and quickly built momentum for action. The BBWG chartered a set of subgroups that were tasked to address different aspects of the problem. Progress has been rapid, with the initiation of several workstreams:

- The Data group secured a grant from the Sloan Foundation and hired a professor of entrepreneurism from Simmons Business School, Teresa Nelson, to identify all the boards served on and companies founded by all faculty in seven departments in MIT’s Schools of Science and Engineering, drawing on public information and a faculty list provided by IR. That work, presented in the next article of this newsletter, documents the stunning lack of participation in commercialization by women faculty in biological sciences and the lack of inclusion of women faculty in Science and Engineering as co-founders and board members of biotech start-ups founded by male colleagues. It also provides a methodology and a baseline from which to measure change.

- Heads of MIT’s TLO and IR had already partnered to collect data on the gender of faculty who file for patents, and on patents licensed to companies. This effort was strongly endorsed by Vice President for Research Maria Zuber, who also requested data on ethnic composition be recorded and reported to the MIT administration. These data should serve to raise awareness of the importance of the issue among faculty and VC biotech founders, and provide a baseline to track trends.

- The VC group agreed to promulgate among the VC community a pledge to aim for 25% women faculty on boards of their biotech start-ups by 2025, a percentage that reflects the percentage of women faculty in the pipeline. The group also proposed a fellowship program to bring women faculty into their firms for short-term VC experience, a proposal quickly endorsed and supported by Anantha Chandrakasan, MIT’s Dean of Engineering, and Nergis Mavalvala, MIT’s Dean of Science.

- The Founder Development group, led by Professor Bhatia, with Professor Lodish and with strong support from Dean Chandrakasan, launched the “Future Founders Initiative,” described in the third article in this newsletter. Despite the pandemic, the Future Founders Initiative attracted over 500 participants to its fall 2020 bootcamp series.

- The Media group facilitated publication of articles in the Boston Globe, STAT, and the Washington Post describing the BBWG initiative and presentations at various regional, national, and international meetings (6).

- Greater Boston Biohub and our regional advantage: If more women faculty become founders and board members of biotech startups, we will not only address concerns about equitable participation but also create other benefits, among them maximizing this region’s potential to drive innovation and healthcare interventions that will improve lives. As Susan Hockfield noted, “Consider the implications of one finding described in the article by the BBWG’s Data group [the article that follows this one in this newsletter]: Even just in the seven departments analyzed in our study, the underrepresentation of women faculty as founders means that some 40 companies were not founded. Missing those 40 companies means missing the clinical interventions that could predict, prevent, and treat disease. Greater Boston hosts the most vibrant bio-hub in the world, but competition for that preeminent position is fierce. We owe it to the world at large to amplify our regional advantage by drawing on all of our talent to change the face of health and healthcare for the world.”

Change hearts and minds or mandate outcomes?

So far, the BBWG’s efforts have focused on data collection and on opening channels for participation by women faculty through the very exciting Future Founders Initiative and VC involvement. But two issues will require additional and distinct efforts, I believe. One is overcoming powerful unconscious biases and homophily (the tendency of people to work with people who look like themselves), the second is the issue of race and, specifically for us, the inclusion of women faculty of color in entrepreneurial activities.

As for unconscious biases, we have not yet designed remedies for the failure of male faculty to include female colleagues in their commercialization activities, nor for the greater difficulty for women faculty of raising comparable funds for start-ups, where many studies have shown that gender impacts funding levels.

At the first dinner meeting of the BBWG, senior women faculty who had founded companies reported that they had been advised that if they wanted to be taken seriously when pitching to VCs, they should include their male students or postdocs, and have the men do “the pitch.”

Almost identical comments have come from women faculty at Stanford, Johns Hopkins, and other universities. These common experiences and the persistent underrepresentation of women faculty in leadership roles in biotech over 40 years have led me to ponder why progress for women faculty in leadership roles in STEM progressed more rapidly within academia than at this academia-industry interface.

Women gained entry to university faculties in the late 1960s and early 1970s thanks to civil rights and legal reform, and societal pressures led by women’s groups. Titles VII and IX also drove change for women students and faculty once they had arrived: Universities were required to provide a level playing field for their students and faculty or risk losing their federal funding. A half century ago, equal opportunity became a legal requirement and a university ethic, with the goal being a diverse student body and faculty. But campus-based requirements and ethics do not apply in the biotech industry, where a more old-fashioned ethic of practice, sometimes called “the old boy network,” still reigns. This poses a problem for MIT.

The biotech start-up industry relies on the university for its life blood. It, and the scientists who found companies and remain on the MIT faculty, are using the university’s valuable resources – its brilliant faculty, students, and postdocs, its publicly funded research enterprise – to seed their business enterprises. By operating as they do, if not providing equal opportunity for women faculty and trainees, as well as for people of color, in this professionally important and potentially lucrative activity, they put the university at risk.

While it was clear from the BBWG dinners that every participant was anxious to fix these problems, we know how hard it is to change behavior and the underlying unconscious biases.

Interestingly, the most radical fix suggested at our dinners came not from academics but from businessmen. One VC noted that the universities could fix this problem quite quickly. University endowments invest heavily in venture funds and could demand that the funds they invest in present evidence of diversity in the leadership of companies they found. Yale’s legendary endowment manager, David Swensen, recently wrote that going forward he will have diversity on his mind when he invests, having been moved by the events around race in the past year, including George Floyd and the differential impact of the pandemic on people of color (7). One hopes his leadership will precipitate robust discussion of this approach.

As for women of color, the issues all women faculty encounter are usually compounded for them by the well-documented “double bind” at the intersection of race and gender. In terms of founders and board members of biotech start-ups, there is also the issue of pipeline to be considered both for female URMs (“underrepresented minorities,” meaning American Indian or Alaskan Native, Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander) and for other women of color.

Of the 675 faculty in MIT’s Schools of Engineering and Science, only six are female URMs. (The 44 male faculty URMs in Science and Engineering represent only 6.5% of the STEM faculty.) These small numbers demand a different methodology to identify barriers and may also require additional approaches to facilitate participation (although it should be noted that all tenured female faculty URMs in Science and Engineering at MIT have participated in entrepreneurial activities). Clearly, it is important that such studies and efforts be undertaken. Our colleague, Helen Elaine Lee, suggested to me that given the small numbers at MIT, it would be desirable to extend the studies to male faculty URMs and to extend our studies of women faculty to specifically consider women of color in other leading research universities in Boston. As for facilitating participation, when numbers are low, recruiting even a few individuals to the leadership level can have an enormous impact by providing role models for trainees. Given the momentum of the group, now would seem a perfect time to do so.

Furthermore, gender inclusion and equity are inextricable from racial inclusion and equity, and a goal of the Future Founders Initiative going forward will be to help the biotech start-up industry reflect the full diversity of Boston’s university faculties and of our society.

It had not occurred to me that in my retirement I would still be working on equity for women faculty. Initially, I was attracted by the opportunity to continue to work with Sangeeta Bhatia, whose passion for translating her discoveries through commercialization, and for furthering the careers of women in STEM, I find inspiring. When Susan Hockfield stepped forward and offered to help us, I agreed to continue our work. A problem as complex as the biotech issue can probably only be tackled productively by someone with Hockfield’s experience and skill. I have been awed – yet again – by her leadership. It has been a unique pleasure, and a privilege to work with both Susan and Sangeeta. I thank them for this experience.

Acknowledgements

I thank Laurie McDonough for advice and her support of the BBWG, John Dowling for many discussions of these issues, Helen Elaine Lee for her insight about how to extend the efforts of the BBWG to faculty of color, Bob Buderi for valuable editorial advice, and Candida Brush for insights about entrepreneurism and venture funding.

References

- Many reports have documented underrepresentation of women in entrepreneurial activities in diverse fields, with some finding that less than 3% of venture funding goes to women nationally. Catalyst, the Kauffman Foundation, the Diana Project, and the EOS Foundation have consistently reported on these aspects of entrepreneurship. Further, many academic articles analyze the reasons why women may be underrepresented. See for example, Balachandra, L., et al. (2019) “Don’t Pitch Like a Girl: How Gender Stereotypes Influence Investor Decisions.” Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, Vol 43(I) 116-137.

- From a report to Dean of Science Bob Birgeneau, entitled “First Report of the Committee on Women Faculty in the School of Science on the Status and Equitable Treatment of Women Faculty,” submitted August 1996, amended February 1997.

- McCook, A. “Women in biotechnology: Barred from the boardroom.” Nature 495, 25–27, 2013.

- Hanes, Serena and Ku, Katharine and Primiano, Lisa and Arvin, Ann, “Gender Analysis of Invention Disclosures and Companies Founded by Stanford University Faculty from 2000-2014” (January 16, 2018). les Nouvelles – Journal of the Licensing Executives Society, Volume LIII No. 1, March 2018. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3103214

- Lodish, H. and N. Hopkins. “Boston biotech has a woman problem.” Boston Globe, Nov 15, 2017.

- Begley, S. “Three star scientists announce plan to solve biotech’s ‘missing women’ problem.” Boston Globe, January 29, 2020; Johnson, C.Y. “Bias in biotech funding has blocked companies led by women.” Washington Post, January 29, 2020.

- Chung, J. and D. Lim. “Yale’s David Swensen Puts Money Managers on Notice About Diversity.” Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2020.